📖 Presidential Profile

Comprehensive overview of leadership, policies, and historical significance

📋 Biography & Political Journey

The Scholar President’s Remarkable Journey

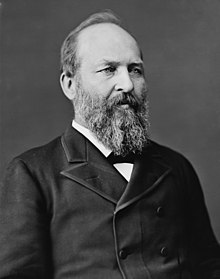

James A. Garfield brought unprecedented intellectual credentials to the presidency, having served as a college professor, mathematician, and classical scholar before entering politics. Born in a log cabin in Ohio, Garfield’s rise from poverty to the presidency embodied the American dream of self-improvement through education and hard work. His academic background included mastery of Latin and Greek, and he was reportedly able to write simultaneously in Latin with one hand and Greek with the other.

Garfield’s political career began during the Civil War, where he served as a brigadier general at the Battle of Shiloh and later commanded Union forces at the Battle of Middle Creek. His military service led to his election to Congress, where he served for 17 years and became one of the most respected Republican leaders. His nomination for president came as a dark horse compromise candidate at the 1880 Republican Convention, reflecting his reputation as a unifying figure.

Civil Service Reform and Political Challenges

Garfield’s brief presidency was dominated by the ongoing struggle between Republican factions over civil service reform and patronage appointments. He aligned himself with the “Half-Breed” Republicans who favored merit-based government appointments, opposing the “Stalwart” faction led by Senator Roscoe Conkling that defended the traditional spoils system.

The president’s appointment of William H. Robertson as Collector of the Port of New York directly challenged Conkling’s political machine and led to a bitter confrontation. Garfield’s refusal to back down demonstrated his commitment to presidential independence from congressional bosses. “This will settle the question whether the President is registering clerk of the Senate or the Executive of the United States,” Garfield declared, asserting executive authority over federal appointments.

Educational Philosophy and Intellectual Pursuits

Before entering politics, Garfield served as president of Hiram College (then called the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute) in Ohio, where he taught mathematics, classical languages, and literature. His educational philosophy emphasized practical learning combined with classical studies, believing that true education should prepare citizens for both economic success and civic responsibility.

Garfield’s intellectual interests extended to mathematics and science. He developed an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem using trapezoids, which was published in the New England Journal of Education. His scholarly achievements made him unique among presidents, and he often incorporated classical references and philosophical concepts into his political speeches, elevating the intellectual tone of American political discourse.

The Assassination and Its Aftermath

On July 2, 1881, Garfield was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, a mentally unstable office-seeker who had been denied a government position. Guiteau believed that Garfield’s death would heal the Republican Party’s factional divisions and that he deserved recognition for his service to the party. The assassination shocked the nation and created widespread sympathy for civil service reform.

Garfield’s medical treatment became a tragic comedy of errors, with doctors repeatedly probing his wounds with unsterilized instruments, likely causing the infection that ultimately killed him. Alexander Graham Bell even attempted to locate the bullet using a primitive metal detector, but the device was confused by the metal springs in Garfield’s mattress. The president lingered for 80 days before dying on September 19, 1881, making his assassination a prolonged national trauma.

The Canal Boat Boy and Mathematical Genius

Before achieving fame as a scholar and politician, young Garfield worked as a canal boat driver on the Ohio Canal, where he reportedly fell into the water 14 times in six weeks. His clumsiness on the water became a source of family humor, but the experience taught him valuable lessons about hard work and perseverance that would serve him throughout his life.

Garfield’s mathematical abilities were legendary among his contemporaries. During his time in Congress, he would often entertain colleagues by performing complex calculations in his head or demonstrating geometric principles using improvised materials. His fellow congressmen were amazed when he simultaneously wrote in English with his right hand and Latin with his left hand while carrying on a conversation in Greek. These intellectual parlor tricks made him a favorite at Washington social gatherings and reinforced his reputation as the most scholarly president since Thomas Jefferson.

Humor & Jokes

Canal Boy to President

Garfield went from canal boy to president. It was the ultimate American dream, if your…

Read More →Greatest Wins

✊ Support for African American Civil Rights and Education

As president, Garfield advocated for federal funding of education and protection of voting rights for…

Read More →Epic Fails

🚨 Inflammatory Anti-Chinese Immigration Rhetoric

Garfield's racist statements about Chinese immigrants fueled discriminatory policies and violence against Asian Americans nationwide.

Read More →