📖 Presidential Profile

Comprehensive overview of leadership, policies, and historical significance

📋 Biography & Political Journey

Revolutionary Leadership and Diplomatic Service

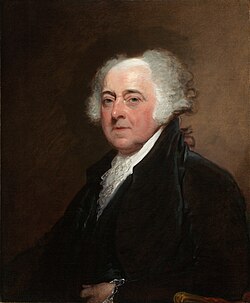

John Adams was born on October 30, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts, to a farming family of modest means. Despite his humble origins, Adams received a Harvard education and became a successful lawyer, gaining prominence for his principled defense of British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre. This unpopular but legally sound decision demonstrated Adams’ commitment to the rule of law, even when it conflicted with popular sentiment.

Adams played a crucial role in the American Revolution, serving in the Continental Congress and advocating forcefully for independence. He nominated George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and was instrumental in persuading Congress to approve the Declaration of Independence. His diplomatic service during the war included successful missions to secure European support, particularly from the Netherlands, and he helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War.

As the first American minister to Great Britain from 1785 to 1788, Adams worked to establish diplomatic relations with the former mother country. His experiences in Europe, detailed in extensive correspondence with his wife Abigail, provided valuable insights into European politics and reinforced his commitment to American independence and republican government.

Vice Presidency and Presidential Challenges

Adams served as the nation’s first Vice President under George Washington from 1789 to 1797, though he found the position frustrating and relatively powerless. He famously described the vice presidency as “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived.” Despite this frustration, Adams used his position to support Washington’s administration and help establish important precedents for the new government.

Adams’ presidency began in 1797 during a period of intense international tension and domestic political division. The Quasi-War with France dominated his administration, as French vessels attacked American shipping in response to Jay’s Treaty with Britain. Adams navigated this crisis by building up American naval forces while avoiding full-scale war, demonstrating his commitment to American neutrality and independence.

The XYZ Affair in 1797-1798, in which French agents demanded bribes from American diplomats, inflamed anti-French sentiment and strengthened Adams’ position. His decision to pursue peace negotiations with France, despite opposition from his own Federalist Party, ultimately preserved American neutrality but cost him political support and contributed to his electoral defeat in 1800.

The Alien and Sedition Acts Controversy

The most controversial aspect of Adams’ presidency involved the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, which his Federalist allies passed during the Quasi-War crisis. These laws extended the residency requirement for citizenship, allowed the president to deport dangerous aliens, and criminalized criticism of the government. Adams signed these acts, viewing them as necessary wartime measures to protect national security.

The Sedition Act was used to prosecute Republican newspaper editors and politicians who criticized Adams’ administration, leading to accusations that Federalists were undermining the First Amendment and establishing a tyrannical government. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, written by Madison and Jefferson, challenged these laws as unconstitutional and asserted states’ rights to nullify federal legislation, setting a dangerous precedent for future sectional conflicts.

The Midnight Judges Appointment Spree

In his final hours as president, John Adams frantically signed judicial appointments until nearly midnight before Jefferson’s inauguration, earning these appointees the nickname “midnight judges.” Legend has it that Adams was still signing commissions by candlelight when Jefferson’s supporters arrived to take over the government. The most famous of these last-minute appointments was John Marshall as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, though Marshall had actually been appointed earlier. Some commissions were delivered so late that incoming Secretary of State James Madison refused to honor them, leading to the landmark Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison. Adams’ marathon signing session reflected his desperate attempt to maintain Federalist influence in the judiciary after losing both the presidency and Congress to Jefferson’s Republicans. The sight of the portly president hunched over his desk, furiously scribbling signatures as the clock approached midnight, became a lasting image of political desperation and partisan rivalry in the early republic.

Humor & Jokes

XYZ Affair

The XYZ Affair nearly led to war with France during Adams' presidency. International diplomacy through…

Read More →Greatest Wins

⚖️ Appointment of John Marshall as Chief Justice

Adams' selection of John Marshall created the longest-serving and most influential Chief Justice, who established…

Read More →Epic Fails

⚖️ Midnight Judges: Packing the Courts Before Leaving Office

Adams appointed dozens of Federalist judges in his final hours as president, creating a constitutional…

Read More →