📖 Presidential Profile

Comprehensive overview of leadership, policies, and historical significance

📋 Biography & Political Journey

Early Life and Military Leadership

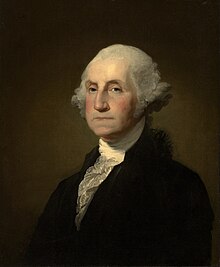

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, into a moderately prosperous planter family. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Washington received only a basic formal education but compensated through practical experience and self-study. As a young man, he worked as a surveyor, which gave him extensive knowledge of the Virginia frontier and valuable skills in mathematics and engineering that would serve him throughout his military and political career.

Washington’s military career began during the French and Indian War, where he served as a colonel in the Virginia militia and gained valuable experience in frontier warfare. His early military failures, including his surrender at Fort Necessity in 1754, taught him important lessons about leadership and strategy. These experiences in the wilderness of western Pennsylvania and Ohio prepared him for the challenges he would later face as commander of the Continental Army.

By the time of the Revolutionary War, Washington had become one of Virginia’s wealthiest planters through his marriage to Martha Custis and his management of Mount Vernon plantation. His social position, military experience, and commanding presence made him the unanimous choice of the Continental Congress to lead American forces against Britain. His appointment as commander-in-chief in 1775 marked the beginning of his transformation from Virginia planter to national leader.

Revolutionary War Victory and Constitutional Convention

Washington’s leadership during the Revolutionary War demonstrated remarkable perseverance and strategic thinking. Facing a better-equipped and trained British army, he adopted a defensive strategy that avoided major confrontations while keeping his army intact. His famous crossing of the Delaware River on Christmas night 1776 and subsequent victory at Trenton restored American morale at a critical moment when the cause seemed nearly lost.

The harsh winter at Valley Forge in 1777-1778 tested Washington’s leadership as much as any battle. His ability to maintain army discipline and morale during this period of extreme hardship, while securing French alliance and support, proved crucial to eventual American victory. Washington’s decision to relinquish his military command after the war, returning to civilian life at Mount Vernon, astonished the world and established him as a modern Cincinnatus.

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Washington’s presence as presiding officer provided legitimacy and gravitas to the proceedings. Though he spoke little during debates, his support for a strong federal government helped secure ratification of the Constitution. His unanimous election as the first president reflected the universal trust Americans placed in his judgment and character.

Presidential Precedents and Challenges

Washington’s presidency established numerous precedents that continue to influence American government today. He created the cabinet system, established the principle of civilian control over the military, and demonstrated the peaceful transfer of power. His Farewell Address warned against the dangers of political parties and foreign entanglements, advice that influenced American foreign policy for over a century.

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 provided Washington’s administration with its greatest domestic crisis, as western Pennsylvania farmers violently resisted federal excise taxes on whiskey. Washington’s decision to personally lead federal troops to suppress the rebellion demonstrated the new government’s authority and willingness to enforce federal law. This show of force established an important precedent for federal authority while maintaining respect for constitutional limitations on government power.

Controversial Hamilton Alliance and Slavery

Washington’s strong support for Alexander Hamilton’s financial program created significant controversy and contributed to the formation of political parties he had hoped to avoid. His endorsement of Hamilton’s national bank, assumption of state debts, and pro-business policies alienated Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who viewed these measures as unconstitutional and favorable to wealthy merchants at the expense of farmers and common citizens.

Washington’s ownership of enslaved people presents the most troubling aspect of his legacy. Despite his private expressions of unease about slavery, he owned over 300 enslaved individuals at Mount Vernon and only freed them in his will after Martha’s death. His use of slave labor to build his wealth, combined with his public silence on slavery’s moral implications, reflects the deep contradictions between American ideals of liberty and the reality of human bondage that would eventually tear the nation apart.

The Denture Dilemma

Contrary to popular belief, George Washington’s famous dentures were not made of wood but rather from a combination of human teeth, animal teeth, and ivory. Washington began losing his teeth in his twenties, possibly due to disease, genetics, or his habit of cracking walnuts with his teeth. By his first inauguration, he had only one natural tooth remaining. His various sets of dentures caused him considerable pain and difficulty speaking, which may explain his legendary brevity in public speeches. The dentures also affected his facial appearance, giving him the slightly puffed-out look visible in many portraits. During formal dinners, Washington often had to excuse himself to adjust his ill-fitting teeth, and he sometimes carried a small tool for tightening the springs that held his dentures in place. One set of his dentures, made by dentist John Greenwood, included a breathing hole and was secured by gold wire springs – hardly the rustic wooden teeth of legend, but far more sophisticated than most people of his era could afford.

Humor & Jokes

Valley Forge

Washington survived Valley Forge with his army. Presidential leadership through frozen feet and empty stomachs.

Read More →Greatest Wins

🏛️ Creation of the First Cabinet System

Washington established the presidential cabinet system, creating an efficient executive branch structure that became a…

Read More →Epic Fails

⚖️ Jay's Treaty Negotiations and Ratification

Washington's support for the deeply unpopular Jay's Treaty nearly destroyed his reputation and intensified partisan…

Read More →